SUCCESSFUL ELEPHANT CONSERVATION

When Systems Protect, Recovery Is Possible

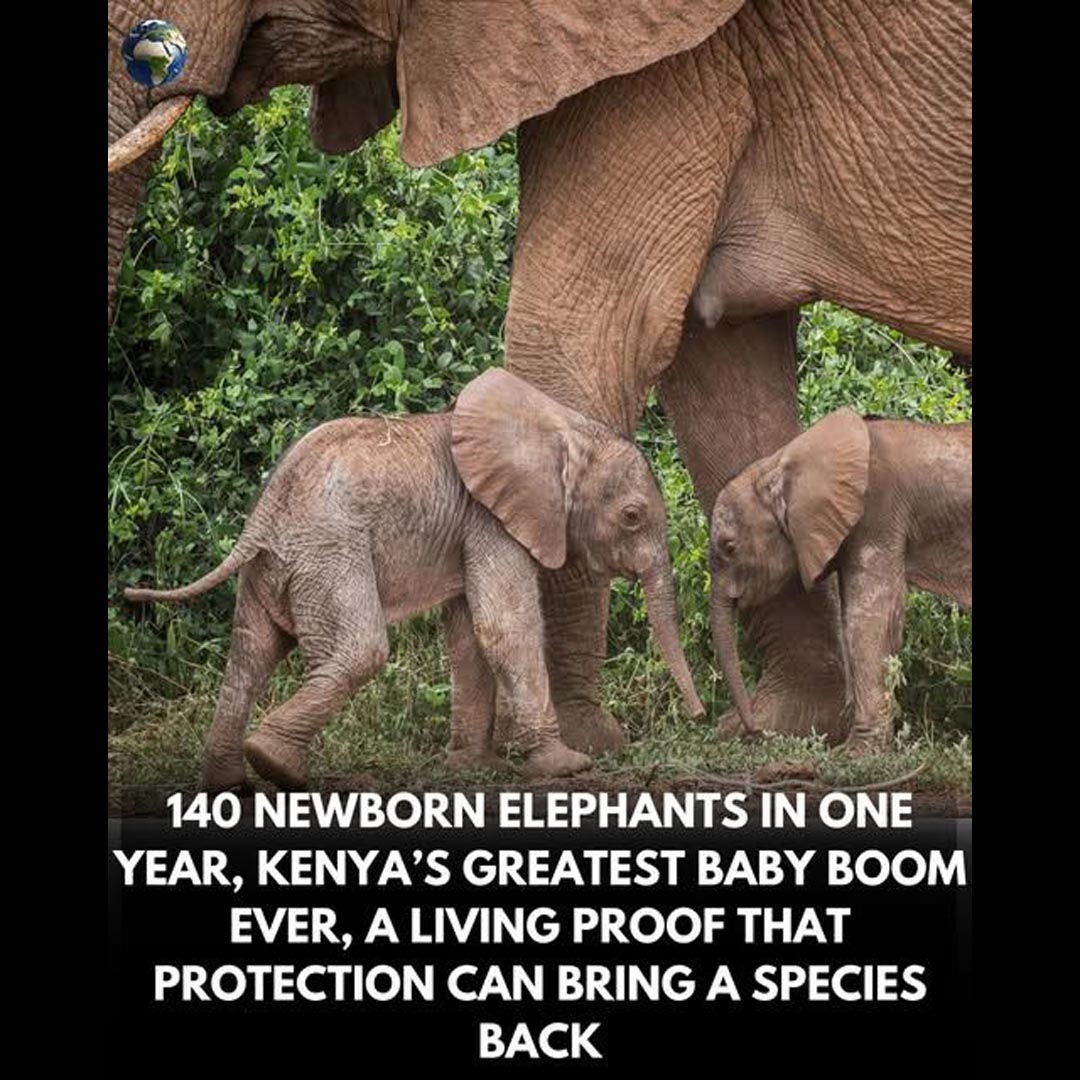

Across Kenya’s savannas, something extraordinary is happening, a surge of new life that wildlife officials are calling one of the greatest conservation successes in modern history. In a single year, 140 elephant calves were born within one national park, a number so high it has shattered previous records and renewed hope for a species that once stood on the brink.

For decades, elephants in East Africa faced relentless pressure: poaching, shrinking habitats, and human-wildlife conflict pushed populations into steep decline. But carefully coordinated conservation strategies – tighter anti-poaching patrols, protected migration corridors, and stronger community partnerships – have finally begun to turn the tide.

Rangers report calmer herds, more breeding-age females, and a rise in experienced matriarchs capable of leading their families safely through the landscape.

What makes this baby boom so significant is not just the number – it’s the timing. Elephants are slow to reproduce (an elephant pregnancy lasts about 660 days, or approximately 22 months), and calves require years of protection to survive. A spike of this magnitude signals real, lasting stability in the ecosystem. It means mothers feel safe enough to raise young, food sources are secure, and threats have been pushed far enough away for family groups to flourish.

Elephants are deeply social, guided by matriarchs who carry decades of memory. When calves arrive in large numbers, it signals more than population growth. It shows that the land is holding, the herds feel secure, and the systems protecting them are working together. Anti-poaching efforts, habitat preservation, and better management of human-wildlife conflict have quietly created space for this to happen. No shortcuts. No single fix. Just consistency, year after year.

The pattern becomes clear here. When ecosystems are given room to recover, life responds with momentum of its own. What’s happening in Amboseli isn’t just a local success. It’s a reminder that recovery is possible when protection is allowed to last long enough to matter.

These 140 calves represent more than population growth. They represent resilience — the ability of nature to rebound when given even a small chance. Each tiny trunk learning to trumpet, each wobbling step beside its mother, is a reminder that conservation is not abstract. It is visible. Countable. Alive.

And the ripple effect stretches far beyond Kenya. Successful elephant recovery boosts biodiversity and sets a precedent for protecting other vulnerable species.

If this is what one protected landscape can achieve, imagine what could happen if every herd had the same safety, the same support – the same chance to grow.

(Note: Amboseli’s elephants are among the most closely monitored in the world, and calf birth and survival rates there are considered a key indicator of long-term conservation health across East Africa.)

Sources: Know Your Planet; Amboseli Trust for Elephants, Kenya Wildlife Service, International Union for Conservation of Nature – as cited in Educated Minds